6 Questions Bond Investors Should Be Asking Right Now

6 Questions Bond Investors Should Be Asking

Right Now

As interest

rates rise, finding the right fixed-income strategy is crucial

https://www.wsj.com/articles/6-questions-bond-investors-should-be-asking-right-now-1494209700

Where can you

get a reasonable return on cash these days? That is one of six questions that

savers and bond investors are asking. ILLUSTRATION: DOUG CHAYKA FOR

THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Michael A.

Pollock

May 7, 2017

10:15 p.m. ET

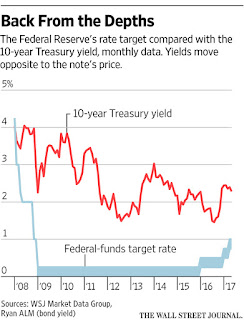

The Federal

Reserve is raising interest rates, and there are several questions that savers

and bond investors would like answered.

For example, to

be blunt: Is my savings

account going to pay any worthwhile interest at some point?! (The

answer: probably not soon. But there are alternatives.)

If this all

sounds familiar, it should: Many bond-market strategists had expected bond

yields would be a lot higher by this point in the economic recovery, perhaps

even making a savings account desirable. But a climb in rates seems to be

getting closer.

With inflation

ticking higher, the Fed now anticipates lifting short-term rates more rapidly.

Officials also are discussing winding down the Fed’s huge bond portfolio,

accumulated during the recession to damp yields. Such a move would eliminate a

major source of demand for government bonds, whose prices fall as yields rise.s vesting

INVESTING

IN FUNDS & ETFS

And meanwhile,

Washington lawmakers are talking about tax cuts and infrastructure spending

that could stoke growth and lift inflation.

Amid such

developments, “you need to be really careful about how you invest the

fixed-income part of your portfolio,” says Terri Spath, chief investment

officer at Sierra Investment Management in Santa Monica, Calif.

She and others

say there are some smarter ways to play this: Avoid putting any cash that might

be needed soon into bonds. Keep additional funds around to invest later, at

potentially higher rates. Dial back on rate-sensitive holdings, and further

limit risk by owning a range of U.S. and foreign bonds.

Here are six

questions for savers and those who own bonds or are considering buying them:

1. What risks do rising rates pose for

bonds now?

One threat is

to short-maturity bond funds and exchange-traded funds, which some investors

may think are immune to rate risk. These commonly have average maturities of

around two years and aim to generate 1% to 2% in annualized yield.

After raising

rates twice since last fall, Fed officials expect to boost rates another five

or six times by the end of 2018, lifting the Federal Reserve’s rate target to

around 2.25%-2.5% from about 1% now.

Bond yields

move the opposite way as prices. Although short-term funds are less affected by

yield changes than those that own longer maturities, many have a rate

sensitivity of around two. If yields rose by one percentage point, that would

result in a 2% decline in principal value—more than an investor would get back

in interest paid by such a fund.

“If you are an

investor who really can’t stomach any losses, you should be in a money-market

fund” where principal value would remain steady, says Emory Zink, analyst at

fund-trackers Morningstar Inc.

2. Where can investors get reasonable

returns on cash?

Although

short-term rates are rising, banks—not the market—decide what rate of interest

they will pay on savings. The national average rate today is just 0.08%, and

banks will raise rates slowly since doing so will boost their profitability.

Some money-market

funds yield closer to 1%. Their yields will rise gradually, though lagging

behind the Fed’s rate increases.

For the best

combination of yield and safety, investors might consider putting money into a

high-yielding, federally insured bank savings account, says Bankrate.com chief

financial analyst Greg McBride. Such accounts are offered by virtual

institutions that are courting depositors. Two such banks, Goldman Sachs Group

Inc.’s GS Bank and the CIT Bank unit of CIT Group, are advertising rates above 1%.

3. Which bonds offer some protection

against rising rates?

One way to

diversify against U.S. rate risk is with bonds issued in other countries whose

rate cycles aren’t in sync with that in the U.S. Raman Srivastava, managing

director for global fixed income at Standish Mellon Asset Management Co., cites

emerging-markets bonds as among “the more compelling opportunities” after

investors fled such bonds several years ago. Yields can top 5%, offering a

bigger offset to the impact of rising yields.

Moving lower on

the U.S. credit ladder is another solution. High-yield bonds (or junk bonds)

issued by companies with weaker credit ratings can yield more than 6%.

But be cautious

about loading up on such securities to the exclusion of higher-quality bonds.

While higher-yielding bonds are less vulnerable to rising yields, they are very

sensitive to worries about defaults and can be volatile, notes Scott Kimball,

portfolio manager of BMO TCH Core Plus Bond Fund (BATCX). In 2015, he says,

some high-yield bonds issued by energy companies plunged in price during the

oil-market swoon.

Fed Chairwoman

Janet Yellen before she testified on Capitol Hill in

February. PHOTO: JOSHUA ROBERTS/REUTERS

4. How can investors lock in better

income as rates rise?

Traditionally

investors did that by building a ladder of bonds having sequential maturities.

As the nearest matured, the proceeds were reinvested in a new bond due to

mature several years later, when the investor hoped to reinvest at an even

higher yield.

Alternatively,

an investor could build a ladder with defined-maturity bond ETFs, says David

Berman, chief executive of Baltimore-based wealth manager Berman McAleer.

Unlike conventional bond ETFs, which periodically buy new bonds to replace

maturing ones, defined-maturity ETFs own bonds with closely bunched maturities.

After all the bonds mature, the ETF repays principal and interest.

Mr. Berman uses

Guggenheim BulletShares ETFs, which are available in either investment-grade or

high-yield corporate versions. BlackRock’s iShares unit offers defined-maturity

ETFs that own taxable corporate bonds or tax-exempt municipal bonds.

5. What are the alternatives to

fixed-rate bond funds?

Floating-rate

funds—sometimes called senior-loan or bank-loan funds—can be a good defensive

play when rates are rising.

ILLUSTRATION: DOUG

CHAYKA FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Such funds own

loans made by banks to companies with lower credit ratings and yield 4% or

more. The rates on the loans periodically adjust up or down, based on changes

in a benchmark index such as the London interbank offered rate, or Libor, so a

fund’s yield moves higher as rates rise.

One concern is

that surging demand for such funds is enabling companies now to get much more

lenient borrowing terms, says Frank Ossino, who oversees Virtus Senior

Floating Rate Fund(PSFRX) at Newfleet Asset Management, in Hartford, Conn.

Mr. Ossino cautions that another downturn eventually could spark defaults on

lower-grade loans, denting a fund’s returns. Funds that yield more than peers

may own a larger percentage of such loans, he says.

Among senior

loan funds that Morningstar rates highly are Eaton Vance

Floating-Rate (EVBLX), Lord Abbett

Floating Rate (LFRAX) and Fidelity Floating

Rate High Income (FFRHX).

6. Are mutual funds or ETFs better at

this point in the cycle?

Active managers

can reposition a portfolio to trim rate risk, moving to bonds that are less

rate-sensitive. But ETFs may be a good choice because they charge much lower

management fees—a benefit at times when bond returns are slim by historic

standards.

Still, people

who plan to buy an ETF need to understand what they are getting, says Josh

Jalinski, an adviser in Toms River, N.J. ETFs that focus on certain narrower

sectors, such as iShares

20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF (TLT), can be volatile, posing more risk of

mistiming a purchase or sale, he says.

Some ETFs hedge

against rising rates. They include WisdomTree Barclays Interest Rate Hedged U.S. Aggregate Bond

Fund (AGZD), which yields about 2%, and Deutsche X-trackers

Investment Grade Bond Interest Rate Hedged ETF (IGIH), which recently

yielded about 3¼%.

Hedged funds

outperform when rates rise, but may underperform when rates are falling, says

Todd Rosenbluth, director of ETF and mutual-fund research at CFRA, a New

York-based provider of investment research. “By hedging, you protect against

something, but also you can miss something,” he says.

Mr. Pollock

is a writer in Ridgewood, N.J. He can be reached at reports@wsj.com.

Appeared in

the May. 08, 2017, print edition as '6 Questions for Bond Investors.'

Comments

Post a Comment