The DuPont Identity: A vital key to understanding the Financial Markets

Friday,

February 17th, 2012

“Knowledge is power.” – Sir Francis Bacon

We

promised at the outset, to deliver an amusing, yet educational experience. On

that note, we unveil today’s feature: The DuPont Analysis.

DuPont

deconstructs and reviews the components that encompass the essential view of a

company’s health, its return on Equity (ROE). It was developed by DuPont in the

1920’s to help them manage their conglomerate, and it is brilliant! The

inspiration to delve into this financial abstruse was the story of Billy Beane,

as portrayed in Michael Lewis’ popular book, “Money Ball”. Beane, the general

manager for the Oakland Athletics baseball team, discovers the usefulness of

viewing major league prospects through the lens of statistical analysis that

goes far beyond the normal batting and earned run average statistics.

Beane,

who was once a baseball prodigy himself, found disappointment through unmet

expectations in his own career. Upon reflection, he comes to realize that the

established method of viewing prospects on simple statistics and body type is

fraught with uncertainty. In his view, the fortune of a team is more determined

by beauty pageant standards and less in hard reality. Beane then subscribes to

a more complete examination that ultimately focuses on players that score, or

prevent runs efficiently. He finds the “Rosetta Stone” that allows the small

market A’s to compete with big budget giants like the Yankees. Beane’s revelation

is that of any idea that is genius: simplicity is ultimately profound. The

object of baseball, like most sports, is to score at least one more run than

the next team. The players that best help a team do that, relative to cost, are

the most valuable. In many respects, Beane’s insights can be applied to

portfolio management.

The

objective when investing, is to better the risk-free rate with as high a return

relative to one’s risk tolerance as possible. In order to do that, one must

discover fundamentally undervalued securities. The DuPont analysis is an

effective tool in beginning that journey.

Many

investors, professional or otherwise, overlook this simple fact. They often

rely on alchemic methods such as momentum, technical analysis or premonitions. Without

a sound basis in valuation, these investments are occasionally correct but

eventually unsuccessful. This methodology is much like that of a gambler whose

luck, in time, runs out. The other extreme is to be overly conservative, thus

falling in a trap where risk taken is not appreciated or rewarded. Witness, for

example, the many investors scorched on supposedly safe mortgage-backed

investments. As we have previously cautioned, stick with fundamental analysis,

or arbitrage opportunities for the most probable road to higher returns

relative to downside potential. To that end, we explore a construct that we

will feature in the future, the DuPont Identity, or Analysis.

Going

back to our “Moneyball” analogy, some measures of profitability cannot be

ignored. Among these are Return on Assets (ROA) or Return on Equity. These

measures of a company’s ability to extract earnings out of its asset base have

long been considered, among savvy investors, as a crucial gauge of a business’s

success. However, both devices, like a baseball batting average, can be

misleading. What DuPont does is break down the components that eventually

comprise ROE and ROA. In the process, it gives the user a fine blueprint as to

how a company generates earnings, and where it needs to adjust its game. We

feel it is an indispensable measure and should be the starting point of any

financial decision.

To

return to our financial roots, ROE is simply net income divided by total

equity. Since equity is the product of assets minus liabilities, you can take

our word and spare yourself the mathematical gymnastics by accepting the fact

that ROE equals ROA magnified by an equity multiplier. The equity multiplier is

simply total assets divided by total equity. This is the amount of debt

relative to equity, or leverage. For example: a company with $1 of debt per 50

cents of equity, would have a multiplier of 1/.5 or 2x. Take the debt, or

leverage, down to 50 cents, and the multiplier drops to .5/.5 or 1x. In effect,

DuPont takes into account the levered effect on a company’s return on assets.

We

next deconstruct ROA considering it is essentially a firm’s profit margin (net

income divided by sales) multiplied by its asset turnover (sales divided by

assets). Finally, we get to the DuPont Identity or: ROE (Return on Equity) =

Profit Margin x Total Asset Turnover x Equity Multiplier

Let’s

examine these components for what they reveal:

Profit Margin (PM): Effectively a firm’s operating efficiency or how much

income results from sales. A high profit margin may seem desirable, however, a

company may be pricing its goods too dear, thus resulting in a higher PM at the

expense of more volume. Conversely, lower expenses may increase net income, but

ultimately cannibalize growth by not reinvesting profits in research and

development. What we are briefly touching upon here are some of the myriad ways

to understand and value a company’s PM.

Total Asset Turnover (TAT): This is a ratio of sales divided by total assets. Again,

this is not as simple as it seems. If, for example, a company has generated $2

of sales from $4 of assets, we have a TAT of .5 times. Another way to view this

is, to divide 1 by our TAT and we get 1/.5 =2. Thus, we need $2 of assets to

generate $1 of sales. The caution here is, that a high TAT is not always a good

thing. A lower value of assets relative to sales may portend that equipment is

getting old and needs to be expensively updated. A smaller TAT, while on its

face a negative, may in fact signal that assets are new, not yet depreciated,

and intact for the long haul. Again, we see DuPont as a starting point for more

meaningful discussions.

Equity Multiplier (EM): As we have already explained, this represents a company’s

leverage. Like any investment, leverage must be carefully calibrated to achieve

maximum results. Too little, and you have not fully realized your potential.

Too much, and you can borrow your way out of business.

Therefore,

we see that a firm can increase its ROE by any number of means. These would

include higher asset turnover, increased margins or greater leverage. Each of

these avenues, present a double-edged sword and should be considered prudently.

When you look at ROE through this prism, the world is more complex, yet

definable. It is with this in mind that we will, in the future, target our

studies. This will give us a conclusive view as to how to truly dissect a

balance sheet in a fashion worthy of a Warren Buffett. In fact, it will be a

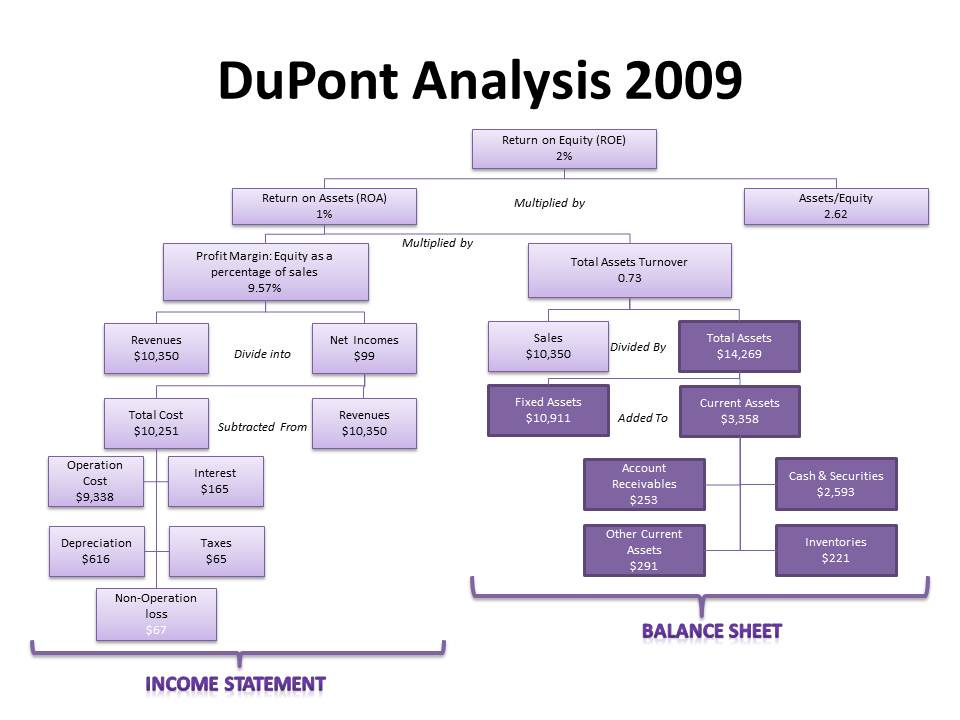

base for many of our investigations, special situation or otherwise. As a final

look regarding which universes we will explore, take a look at an exploded view

of DuPont :

Here,

then, is our foundation for studying many of the balance sheets we will

encounter. Through this method, as the intellects at DuPont understood, is a

thorough and comprehensive flowchart that leads to well contemplated financial

decisions.

Perhaps

this edition of The Thoughtful Arbitrageur may have been a bit

mind-numbing and not as entertaining , but it is necessary if we are to advance

our grasp of the financial markets. Or as your mom would say, “something

valuable is worth working for.”

Jeremy Lin: Black Swan

Much

has been written in the last few days about Jeremy

Lin and we, too,

will add our opinion. First off, we are fervent sports fans due to the purity

sports offers. Athletic competition gives us a chance to view man’s

unadulterated quest for perfection. Here, the warriors are stripped bare and

there is no denying their achievements and failures. It is a beautiful thing to

behold. In fact, this is what we adore about the Jeremy Lin story.

Lin,

a supposed everyman, is one who comes to the field of battle against forces far

greater than he, and wins. The play “Damn Yankees,” or the biblical story of

David and Goliath” come to mind. Yet, Lin’s accomplishments are the very

definition of a “Black Swan”—unpredictable events that are, in hindsight, more

probable than originally thought.

Lin,

while a walk-on for Harvard University’s basketball team, hardly defined the

prototype of an NBA star. Many commentators marvel at the fact that he is the

rare Chinese-American (his parents are from Taiwan) who is succeeding at the

sport. However, Lin is not of a different species. He has the same tools, more

or less, as everyone else. He just chose to make the most out of them and not

let stereotyping dictate his future. That work ethic is probably what got him

into Harvard and will propel his success. This story is a lesson for anyone who

would let circumstance determine their fate.

That’s

enough pontificating—we have to stop and go watch the Knicks game.

Sometimes

it’s a layup and other times a three pointer—but it’s all fun and games….

—

The Thoughtful Arbitrageur

Comments

Post a Comment